Youth Fair in Texas

A professional bull rider has d**d after being trampled during a rodeo event in Texas, according to the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA). Dylan Grant, 24, was…

Rick Harrison Opens Up About Son’s Tragic Death

Fans of Pawn Stars are devastated over recent news. During the early morning hours of January 20, Rick Harrison, the beloved star of Pawn Stars, made a…

The superstar invited a young girl to sing, and within seconds, she captivated the audience, bringing down the house with her performance.

In the spotlight, a young girl, a mix of nerves and determination in her gaze, stepped forward. The megastar handed her the microphone, asking, “Do you know…

Photos That Were Never Edited

Step into the past with a treasure trove of vintage photos featuring celebrities and remarkable figures of yesteryear. From glamorous movie stars to edgy rock icons, these…

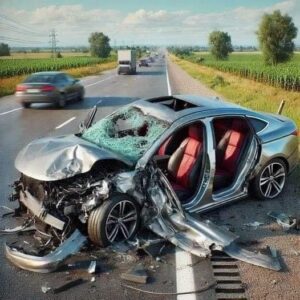

A well-known actress has tragically passed away in a car accident

A fatal car accident claimed the life of 22-year-old Kamylla Cristina Rosa de Oliveira, an actress, a model, and social media influencer from Brazil. The young woman…

FANS Sending Prayers for the Great Singer Keith Urban and his Family…

Keith Urban’s life, marked by a romantic whirlwind with Nicole Kidman and significant philanthropic work, showcases a depth beyond his musical acclaim. Their romance, sparked at “G-Day…

Bruce Willis’ wife Emma Heming shares heartbreaking video of him after his dementia diagnosis

Actor Bruce Willis was diagnosed with aphasia, which impairs communication. His family revealed his condition has progressed to frontotemporal dementia (FTD). “Our family wanted to start by…

It is with great sadness that we announce that the prince has passed away suddenly tonight

Prince Michael of Greece and Denmark – Prince Philip the Duke of Edinburgh’s first cousin – has died at the age of 85. The royal was pronounced…